This article was written for the American Water Resources Association Washington Section (AWRA-WA) Fall 2023 newsletter. Check out the newsletter online and attend the AWRA-WA Section Annual State Conference on Sept. 28!

Author: Greg McLaughlin, Program Director

There is a theory in evolutionary science called the “Red Queen Effect”, borrowed from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass. Alice is with the Red Queen in Wonderland, running as fast as she can, but notices she is not getting anywhere. The Queen notices her struggles and says, “If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast.”

The metaphor is explaining Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory that “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change”. It is also instructive for water resource professionals trying to build resilience in aquatic ecosystems facing increasing frequency of record temperatures and catastrophic drought.

2023 began with promise for Washington’s rivers and streams. A series of healthy snow events left Washington’s watersheds near or above average snowpack as late as April 2023. Reservoirs were full, soils were refilling with slowly melting snow, and Washington skiers were enjoying the slopes later in the season than usual. Those of us who work in water breathed a sigh of relief. 2023, we thought, would be different from recent years, because it would be “normal.” Not like 2021, or 2019, or certainly not like 2015—the hottest, driest summer in Washington’s recorded history.

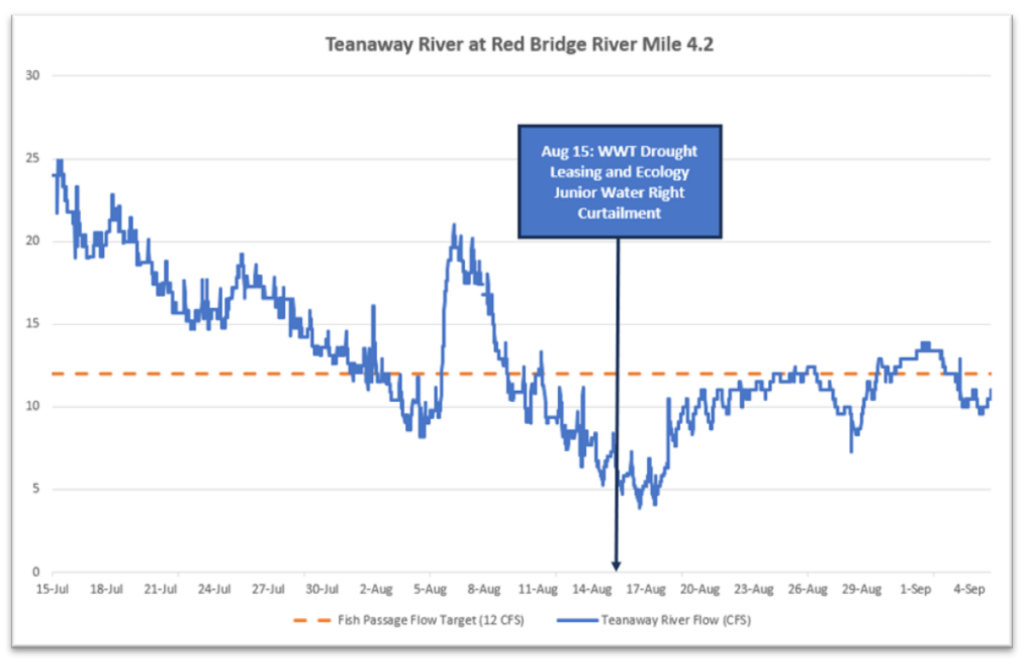

Fast forward to August 2023, when Washington Water Trust (WWT) received an email from Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife fish biologist Jonathon Kohr, who’s part of a team that measures flows in the Teanaway River, one of the most important salmon and steelhead-producing tributaries in the Yakima Basin. “It’s odd,” Kohr said, “this is one of the worst years we’ve measured out there looking through our records.” The Teanaway dropped below 6 cubic feet/second on August 16th—the lowest reading since the drought of 2015—which was the worst in recorded history. All of a sudden, drought had gone from off the radar, to flashing warning signs, to near-record intensity, all in a few months.

What happened? A record-setting heat wave slammed into Washington in mid-May, with above-average temperatures and limited precipitation persisting statewide throughout the summer. From April 15 to May 15, water held by snow in Washington’s watersheds dropped from near-normal levels to near zero in most of the state.

These issues are not localized, or due to normal variations in weather. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported recently that the average July 2023 global temperature was the hottest in recorded history. Records go back to a decade before the US Civil War. July 2023 was the 533rd consecutive month with average global temperatures above the average for the 20th century. This does not happen by chance. The climate is warming quickly, with dramatic consequences for Washington’s streams, their aquatic life, and the water resource professionals working to respond.

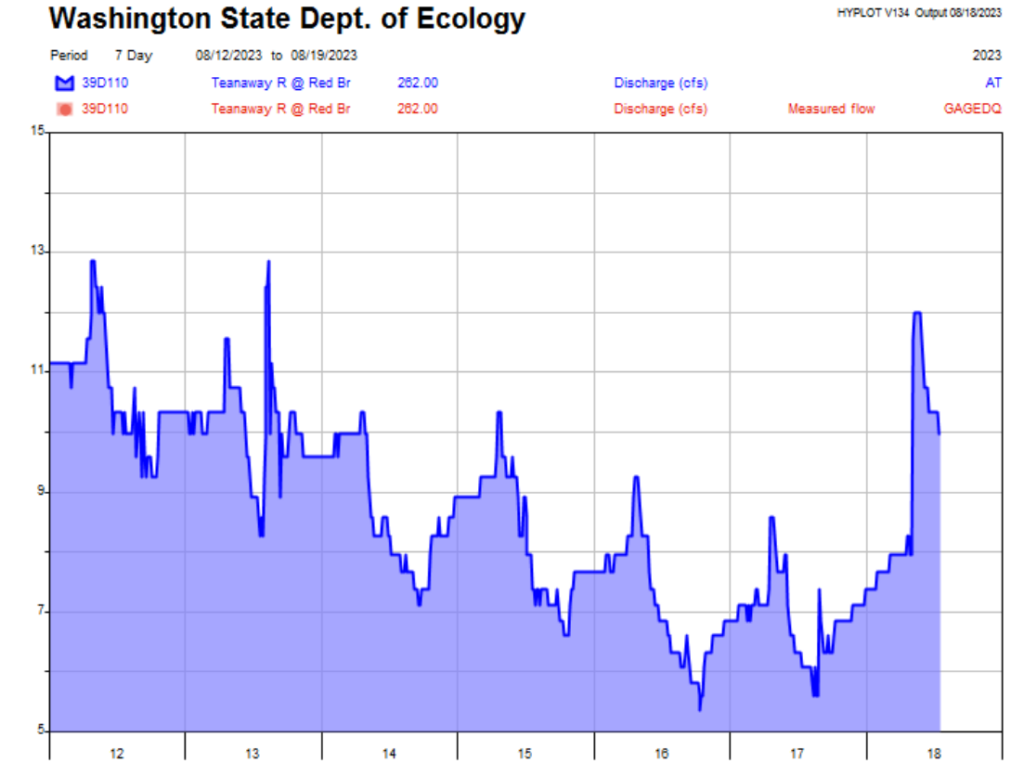

To illustrate this, here is a hydrograph of the August 2023 gage readings for the Teanaway River, a critical steelhead tributary in the Upper Yakima Basin.

This shows flow in cubic feet per second in the Teanaway River from August 12 to 18, 2023. When flows drop below 12 cubic feet per second (cfs), fish cannot easily navigate critical riffles between pools in the river, a key strategy for surviving low flows and high temperatures during drought. If the Teanaway maintains these flows, the fish will (mostly) survive.

WWT, who has been working on trust water projects to restore streamflow since 1998, began worrying about the Teanaway and other critical streams during the May 2023 heat wave. Dropping flows in fish-critical rivers and streams were looking much like they did in the last severe drought year in 2019, four years after the even more extreme drought of 2015. We predicted that these rivers were going to drop to lethal levels and began strategies to mitigate the impacts of extreme drought.

When flows began approaching critical levels in late July, WWT implemented strategies for drought response, implementing programs in the Teanaway and Dungeness Rivers. This combined late-season leasing of water rights with an expectation that the Washington State Department of Ecology (Ecology) would curtail junior water rights to protect instream flow rules and trust water rights previously acquired into the Washington State Trust Water Rights Program. In the Dungeness River, WWT partnered with Ecology, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, and irrigation districts to add nine cfs of drought leases and three large pulse flows to the Dungeness River. This supported fish passage and sustained Dungeness River flows as they dropped below targets set by the basin-wide instream flow rule. In the Teanaway, WWT entered into short term leases from August 15 to September 15 with three landowners that further reduced diversions from the Teanaway. Meanwhile, Ecology curtailed junior water users to protect previously acquired trust water. As the monitoring data below shows, this resulted in allowing the Teanaway to meet and maintain flows near the 12 cfs flow target (dotted line).

The Teanaway tells a story of how coordinated efforts can create resiliency in streams impacted by heat and drought, but there is much work to do. It just takes one extreme event in one stream to wipe out most of a population of salmon in a single year. In such an event, few of the fish that might be genetically adapted to survive in warmer water will survive and pass their genes to the next generation. The climate will change faster than they can evolve. Developing restoration strategies that simply keep up with these drought events is like Alice running as fast as she can to stay in one place.

Recovering species and improving stream health amidst climate change, however, is another challenge altogether. As we try to recover degraded rivers and declining fish populations, we have to build both resilience against change while also making progress on recovery goals. We’re not where we need to be yet, and if we want to get there, we must learn how to run twice as fast.