“We’re not wired for ‘Kumbaya’ here,” says a smiling Mike Tobin, district manager of the North Yakima Conservation District. But he has a good reason to celebrate. Mike is part of a collaboration that has launched a struggling creek on a water-fueled renaissance.

If you’ve ever shopped in a North American supermarket, it’s likely you’ve picked up something grown near the town of Selah on the east side of the Cascade Range in central Washington—an apple, a pear, some cherries; maybe a juice box.

The Matson family has been in the business of growing tree fruit here for well over a century. On a portion of their property, the land was traditionally irrigated by making a temporary “push-up” dam in Nile Creek each year to send water by gravity into a holding pond where a pump would then deliver it where needed. “During low flow, the entire creek and its fish could end up in the pond and in the fields,” says Mike. R.R. Matson Sr., the company founder, who was known to try and rescue as many of those fish as he could.

Now, the third generation of Matsons has closed the loop. “One of the most rewarding elements of the project was their willingness to work with us,” Mike says.

The family entered into an agreement with Washington Water Trust (WWT) to dedicate all of their water right—the only one on the creek—as permanently protected flows. Their new source of irrigation on the Naches River, plentiful and reliable, is aided by the Conservation District, which paid for a pump station and pipeline, and eliminated the old diversion.

The Matson’s property encompasses the length of the stream corridor starting just paces above where Nile Creek joins the Naches and extending more than a mile to public lands of the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. In this reach, an increase of more than 1,500 gallons-per-minute can nearly double the volume of water during the driest days of summer. With support from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Columbia Basin Water Transaction Program, the infusion of flows is a biological game-changer that ripples through the entire stream system, about 15 miles of habitat.

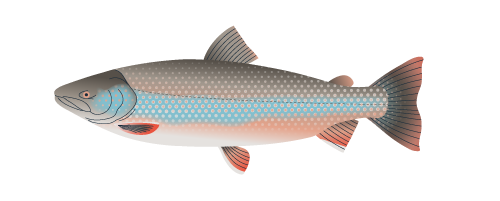

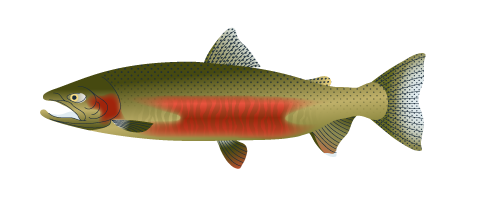

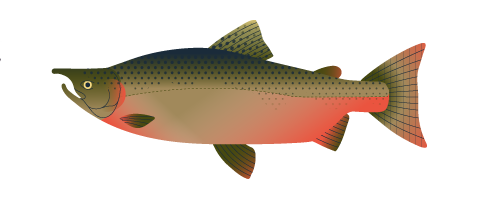

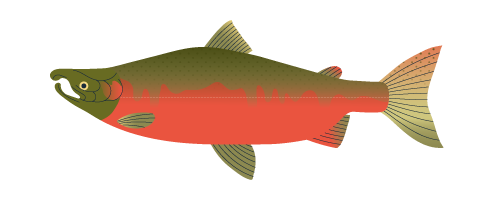

Kris Ribellia, WWT Project Manager, calls Nile Creek a “significant spawning sanctuary” that now provides unhindered migration for threatened steelhead from the creek’s headwaters down to the Naches River. The project makes Nile Creek accessible for coho salmon, too, which are being reintroduced by the Yakama Nation. Spring Chinook and bull trout can also benefit from a creek that is once again reconnected year round to a healthy, spring-fed floodplain.

Gary Torretta, district biologist with the Forest Service, has tracked spawning steelhead in Nile Creek for over a decade. He says the cooler water of new flows will make a qualitative difference at a fragile moment in the steelhead’s lifecycle, just as incubation of eggs is ending and fingerlings are wiggling free from the gravel. These will be healthier fish, with higher rates of survival…and return.

“The rewards for this project can be seen on the ground, here in the creek,” Mike says. “The real indicator will be long-term sustainable populations of anadromous fish that depend on the water mother nature naturally delivers. I have every confidence in the outcome. You add water, fish do better and natural stream process comes to life.” – Written by Jeff Hersh in 2015 for the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.